Editor's note: Louise

Cooper is a financial blogger and commentator who regularly appears on

television, radio and in print. She started her career at Goldman Sachs

as a European equity institutional sales person and then become a

financial and business journalist. She now writes CooperCity.

London (CNN) -- Brilliant minds across the financial world are still trying to work out the implications of the Italian election result.

For the time being, the

best answer is that it is probably too soon to tell. After Tuesday's

falls, a little stability has returned to markets, possibly because

everyone is still trying to work out what to think.

Credit ratings agency

Moody's has warned the election result is negative for Italy -- and also

negative for other indebted eurozone states. It fears political

uncertainty will continue and warns of a "deterioration in the

country's

economic prospects or difficulties in implementing reform," the agency

said.

For the rest of the

eurozone, the result risks "reigniting the euro debt crisis." Madrid

must be looking to Italy with trepidation. If investors decide that

Italy is looking risky again and back off from buying its debt, then

Spain will be drawn into the firing line too.

Can the anti-Berlusconi save Italy?

Louise Cooper, of Cooper City

Standard & Poor's

stated that Italy's rating was not immediately affected by the election

but I think the key part of that sentence is "not immediately."

At the same time Herman

Van Rompuy's tweets give an indication of the view from Brussels: "We

must respect the outcome of democratic elections in Italy," his feed

noted.

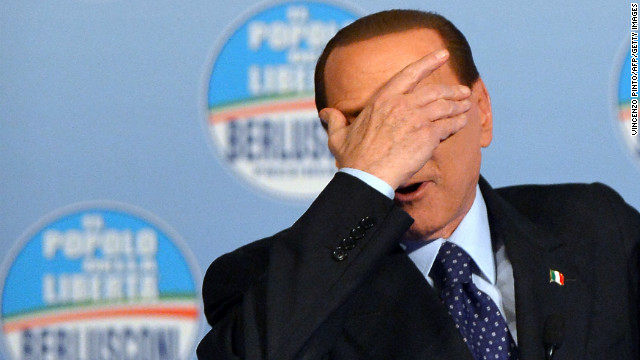

Really? That's a first. The democratically elected Silvio Berlusconi was

forced out when he failed to follow through with austerity after the

European Central Bank helped Italy by buying its debt in autumn 2011.

The clown prince of Italian politics

"It is now up to Italian

political leaders to assume responsibility, compromise and form a stable

government," Van Rompuy tweeted.

Did he see the results? The newcomer and anti-establishment comedian

Beppe Grillo refuses to do a deal and yet he is the natural kingmaker,

polling at 25%.

"Nor for Italy is there a real alternative to continuing fiscal consolidations and reforms," he continued.

Economically yes, but the Italian electorate disagree. And for the time being, Italy has a democracy (of sorts).

Finally: "I am confident that Italy will remain a stable member of the eurozone."

He hopes...

The key to whether the

crisis reignites is whether investors begin to back away from lending to

Italy. If so, this will be the big test of the ECB's resolve to save

the euro.

The key thing to look at

is Italian bonds, because if borrowing costs rise from 4.8% for 10-year

money currently to nearer 6%, then Italy will start to find it too

expensive to borrow.

The trillion euro

question is if the ECB will step in to help even if it cannot get the

reforms and austerity it demands (because of the political situation).

That is the crux of the matter. And there will be many in the city today

pondering that question.

Clearly in financial

markets, taking on a central bank is a dangerous thing to do. Soros may

have broken the Bank of England on Black Wednesday 1992, making billions

by forcing sterling out of the EMU, but that was a long time ago.

Italy avoids panic at bond auction

What we have learnt from

this crisis is not to "fight the Fed" (or the ECB). Last summer, the

ECB's chief Mario Draghi put a line in the sand with his "whatever it

takes" (to save the euro) speech.

But as part of that

commitment he stressed time and time again that any new help from the

ECB comes with conditions attached. And those conditions are what have

proven so unpalatable to the Italians -- austerity and reform.

So we have two

implacable objects hurtling towards each other. The political mess of

Italy and the electorate's dislike of austerity and reform (incumbent

technocrat Mario Monti only polled 10%).

So what happens next?

The status quo can continue if Italian borrowing costs do not rise from

here and therefore Italy does not need ECB help.

If markets continue to

believe in Draghi and Brussels that the euro is "irreversible," then

investors will continue to lend to Italy. Yes, markets will be jittery

and fearful, but Italy will eventually sort itself out politically.

The big advantage for

Italy is although it has a lot of debt, it is not creating debt quickly

(like Greece, Spain or even the UK). And as I said yesterday on my CooperCity blog, the positive outcome from all this could be that Brussels backs off from austerity, which would be a good thing.

However, the basic rule

of finance is that high risk comes with high return. Soros took a huge

gamble against the British central bank but it reportedly made him a

billionaire overnight.

There must be a few

hedge funders looking at the Italian situation with similar greed in

their eyes. If he wants to save the euro, it is time for Mario Draghi to

put the fear of God back into such hearts.

No comments:

Post a Comment